Blog

Blog

A. Iniesta: "The Tecnapur system offers us very positive results"

18th December 2019 - Success stories

As a descendant of a household devoted to cattle rearing, Aitor Iniesta decided to continue with the family business. However, fascinated by the greater complexity illustrated in the reproductive stage of sows, he chose to be trained in this field and run his own sows farm. Convinced of the need to build an environmentally sustainable sector, in 2019 Aitor has invested in the establishment and set up of a slurry treatment plant, which operates the TecnaPur mechanical separator (Phase I) and physicochemical reactor (Phase II), with outstanding results.

How is the farm distributed?

In one section I have the core of breeders with 3,000 sows, with replacement (which we do internally in the farm), gestation and maternity wards where we have piglets up to 6 kilos (26 days of life). Besides, about 3.5 kilometres away, we have the weaning/transition section of up to 20 kilos. Once they have reached this weight, we distribute the animals to fattening farms: one part goes to the family farm, with 7,000 places, and the rest to other farms of the integrator with whom we work.

How many people work on the farm?

We are a team of 25 people. In the breeding section, there are about 17 employees; two in transition, one administrative; two employees for the slurry management of all centres, field treatment and corpse management, two employees for maintenance (one inside the farm and another outside), and I.

This year you decided to install the TecnaPur slurry treatment system, with the mechanical separator and the physicochemical reactor. Why?

Mainly because of a personal principle to have an environmentally friendly farm. Although we do not presently have any complications with slurry because we are in an area with low pig density, I believe that for the livestock and pig production to move forward one must invest to be as environmentally friendly as possible.

Why did you choose the Rotecna system?

I had been looking for a facility that would allow me to enhance nitrogen management, reduce ammonia emissions and the odours that the farm might generate, even though it is far from any metropolitan centre. Therefore, we considered a couple of options and Rotecna, regarding economic viability and functionality, was the one that best fit our purposes. Thus, in April, we equipped the plant, and we are the first slurry treatment plant of these characteristics in Spain. Finally, after the first few months, with the advice and support of Rotecna's technicians, in September, I began to manage the operation of the entire plant myself.

Slurry treatment plant with mechanical separator and physicochemical reactor. Photo: Rotecna.

What has the plant performance been in these first few months?

So far the results are remarkably favourable, as I foresaw: reduction of odours and volume, segregation of nutrients, savings in the cost of extending the slurry, decrease in ammonia emissions, obtaining a quality organic fertiliser for our fields from the solids section. We, as well as breeders, are farmers, so the manure we take out of the slurry is used in our fields as an organic complement; it is a much higher quality organic fertiliser than the synthetic or mineral fertiliser that is ordinarily employed. Now, the next test I want to perform is to use the liquid part for fertigation in adjacent plots. The truth is that this plant offers a broad range of possibilities which, from an environmental perspective, we believe is the model to follow for the future of livestock farming.

What would you highlight about the operation of the physicochemical reactor?

It is a wonderfully intuitive system and suited to any user profile. In our case, we utilise the reactor from Monday to Friday, about ten/eleven hours a day, from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. In this way, on Monday morning, we prepare the flocculant tank, so that once full, we can let the liquid phase that comes out of the mechanical separator transfer into the reactor. With this very simple start-up, automatically and according to the inlet flow, the reactor starts to work. Then, the only thing we usually do is that every two hours, one of the people who is out dealing with the slurry checks that everything is working correctly.

In any case, the safety systems installed in the machine imply that an incident or the end of a chemical product would make the plant stop. Finally, on Fridays, at the end of the week, the flocculant tank must be emptied, and the machine cleaned.

The reactor offers the possibility of remote control; what do you think?

A success. Furthermore, it has a very intuitive administration for anyone moderately versed in new technologies. Specifically, the remote control of the reactor allows me to check on my mobile phone from anywhere and in real-time. I can see what state the machine is in if there is any incident, any alarm, monitor how the system is working, how many cubic meters are entering and what the pH level of the slurry coming out is. You can review absolutely everything, wherever you are. It's a tremendous advantage that also helps you reconcile work and family life.

In numbers, how many cubic metres of slurry do you treat per day?

With an average running time of approximately 11 hours, between 60 and 70 cubic metres of slurry can be processed per day, depending on how dense it is.

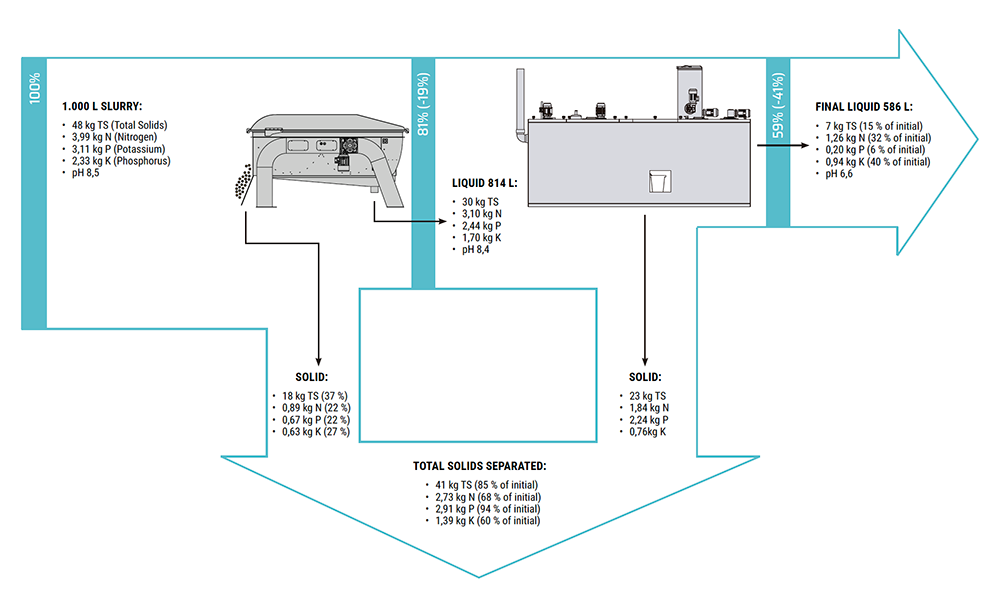

Mass flow diagram of the treatment plant

The different performance and reductions differ according to the composition of the initial slurry.

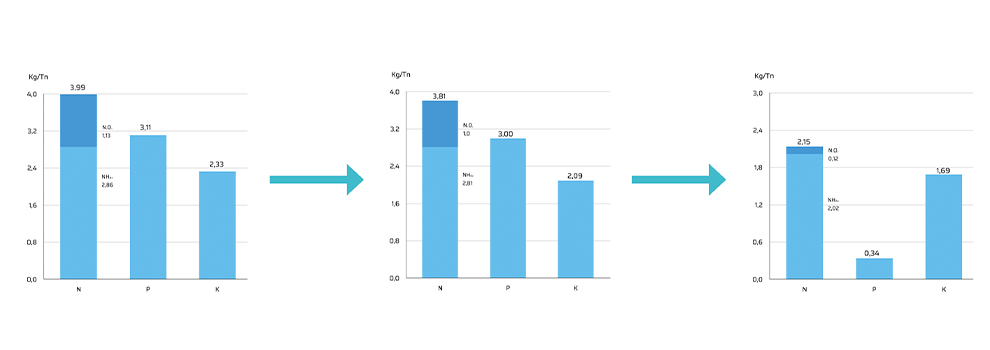

Composition of the liquid phase

And as for the initial volume, what percentage do you get from each portion?

On the farm, we are very mindful of the sensible use of water; every day, the maintenance person checks consumption and checks for possible leaks, so we have a reasonably dense slurry. From there, with the first phase of TecnaPur (mechanical separator) we have a reduction involving the initial volume of 10% that comes out with the solid part, and 90% goes to the liquid portion. Later, in phase 2 (physicochemical reactor), we achieve a solid part of approximately 20-30% and a liquid fraction of 70-80%. As a result, we can reduce nitrogen around 70%, potassium 60% and phosphorus 97% from the initial slurry to the final slurry, with no emissions of ammonia or any other greenhouse gas into the atmosphere.

What do you do with each of the separate parts?

We use the solid part for the vineyard fertiliser, which is the prevalent crop in the area, providing plants with more sustainable and ecological nutrients than the synthetic and mineral fertilisers that are customarily employed. And we use the liquid part to fertilise almonds mainly, as well as dry cereals. In this sense, having separated the majority of solids in suspension from the slurry, the amount of cubic meters that we can apply per hectare increases by 70%, and the amount of total liquid to be transported is reduced by 33%. This means a significant reduction in the extension of crops needed to manage the liquid fertiliser and significant savings in transport.

Aerial view of the Utiel farm (Valencia). Photo: Expoinor

At the farming level, what is the cost per cubic metre of separation?

We do not have an accurate estimate of all the costs. Still, the estimation we have done gives us an approximate price of about 2 to 5 euros per cubic meter in the processing, to which the cost of distributing the product in liquid to spread on farms or for use in drip irrigation should be added as well. As a result, since we can deliver more per hectare and less quantity in total, it is possible to do it closer to the farm, which considerably reduces application costs; therefore, the total cost of the treatment plus the application is calculated to be around 2.3 - 2.8 euros/m3.

Is the financial perspective favourable?

Regarding the costs before separation, yes. Initially, a small extra cost is expected when investing, but then you have a yield on the fertiliser that you are generating with the solid part. However, previously we had costs of 20,000 euros per year for our properties. Now we are saving that, and if we manage to have a surplus of fertiliser, we could sell it and obtain a monetary benefit. Therefore, the extra cost that the plant can generate for the treatment of the slurry is justified and covered by the income that can be obtained from the organic fertiliser and the savings in the transport of the liquid phase. This is because we have to spread less and when we do, its closer. From my point of view, this investment is justified. What is more, we are emphasising the importance all farmers become aware of the need to produce in such an environmentally friendly way.