Blog

Blog

Strategies to reduce neonatal mortality of piglets

21st April 2022 - Studies

Josep Rius. Rotecna R+D Department.

I sometimes visit sow farms and in some of them, I observe a fact that catches my attention: in the maternities the sows give birth unattended. I always wonder why and I don't understand it. If we define neonatal mortality as that which occurs during the seven days after birth, we will realise that it is one of the parameters with the greatest weight in the total profitability of farms, since it represents between 10 and 20% of their total costs (Manteca y de la Torre, 2004). The same authors claim that in Europe 50 million piglets are stillborn or die before weaning every year.

With this data, it is clear that there is room for improvement. It is not accurate to give mortality rates of live deliveries at weaning of about 15% or more. This parameter must be improved because there are farms that are between 5 and 10%. How do they achieve it? Mainly focusing their efforts on the care of deliveries and the 48 hours after, in which, again, the data of many farms tell us that the highest percentage of casualties is concentrated.

In recent years, genetic evolution has led to a considerable increase in the prolificacy of sows. However, this improvement in prolificacy is accompanied, in many cases, by more physiologically immature piglets, which translates into piglets with less birth weight, less vigour, less thermoregulatory capacity and a greater risk of hypoxia and its consequences during delivery. To all this, we must add that the sows have not evolved with the same intensity in their maternal attitudes or aptitudes or in their ability to wean more numerous litters, which has forced farmers to apply all kinds of strategies, mainly food or management, to save the maximum number of piglets.

"Caring for animals to try to save them requires specific knowledge, skills and attitudes."

We agree that facilities, equipment or means are tools that help - each farm or farmer has their own - but the important thing is that the people who have these jobs also have the necessary knowledge to know, in any situation, how they should do their job well, are aware of their importance and, above all, they like to do it.

I have been fortunate to convey how to do this work and you immediately realise who has the talent and sensitivity necessary to develop it. It's like thinking that everyone is used to being a nurse. Is it clear to everyone that this is not the case? Well, in this case, the same thing happens. Caring for animals to try to save them requires specific knowledge, skills and attitudes that not all people can achieve satisfactorily. It seems very basic, but it's always good to remember.

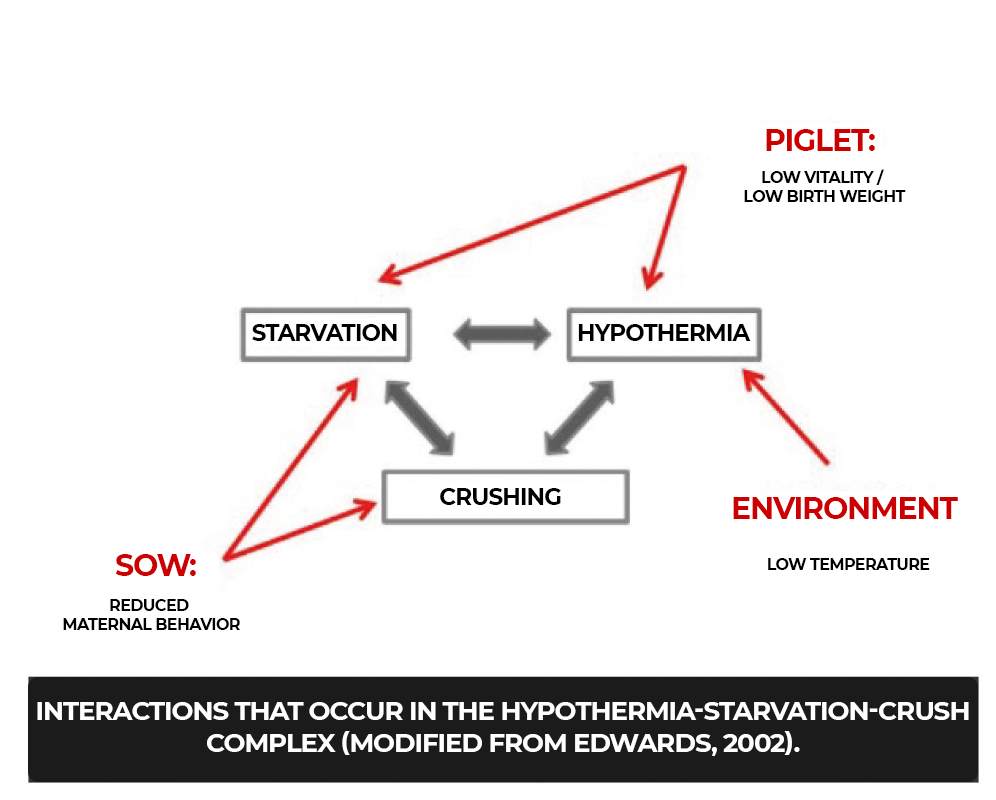

There is a lot of scientific literature on all factors related to neonatal mortality. In this article, we will only focus on providing suggestions to reduce the percentage of crushed, hypothermic and death from starvation, three interrelated aspects that are usually, in most farms, the main causes.

Complex hypothermia - starvation - crushing

If a high percentage of crushing casualties occurs from birth until 2 or 3 days later, it is usually mostly related to hypothermia and starvation. This pattern can be modified if action is taken in time. Depending on the environment they are in at birth, their weight and their vigour, piglets will need more or less help. As we already know, the piglet when it is born has the instinct to go to suckle but has very few energy reserves to do so (fat, glucose and glycogen). If we add to this fact that in the uterus it is at a temperature of between 38 to 40 degrees and outside it is found with an environment well below 32/35 degrees (critical ambient temperature of the piglet) and, in addition, we add that it is born without hair, with a very thin layer of fat, an immature thermoregulation system, wet and small, we already have the set of elements to understand that if they do not reach the energy source that will provide them with the intake of colostrum soon, they will consume the little energy they have in trying to increase their body temperature and the glucose concentration in their blood will drop to levels that will cause death. This process will be faster or slower depending on the environment temperature, the weight, the vigour, the reserves that the piglet has and its placement (if it arrives) in the udder of the sow for its first colostrum suction (Graphic 1).

Graphic 1. Complex hypothermia - starvation - crushing.

In acute or rapid processes, they do not reach the udder. In the slowest, weak piglets must compete with the strongest, which will have already occupied the best and find a free one (if there is one) to ingest colostrum, which only occurs for a limited time (24/48 hours) and whose qualities deteriorate very quickly: it is estimated that 12 hours after calving only 30% of the antibodies are absorbed. To this, we must add that the intestine of the piglet is reducing the absorption capacity of immunoglobulins very quickly.

Handling: avoid loss of body temperature

As we have seen, the arrival to the world of a piglet is an obstacle course against the clock that most manage to overcome. Others do not. If we focus our efforts on these, how could we help them? In an ideal situation, the piglet should lose the minimum possible body temperature at birth and become collusive as soon as possible. Therefore, depending on the delivery room temperature (you have to take into account the time of year) the intervention of the caregiver will be more or less urgent so that they do not lose it. Good management at these points includes recovering the hypothermics as quickly as possible in a comfortable space with high temperatures (36/38 degrees), drying them and, once recovered, placing them in their sow's udder.

Management: colostrum in shifts

Once recovered and located in the udder, small piglets should have a preference for suckling. To do this, a good habit is to heat them in turns. To get it right, the following guidelines should be followed:

- There should never be more piglets in the udder than breasts available.

- Divide the litter into two groups: large and small.

- Mark and lock up the big ones for 90 minutes to give the little ones priority. Then exchange them (the big ones have enough with 45 minutes), and so on until they are all well heated.

- Do not leave only the little ones (if they are few) in the udder (low stimulation capacity of the breasts). Preferably, place the little ones on the front nipples.

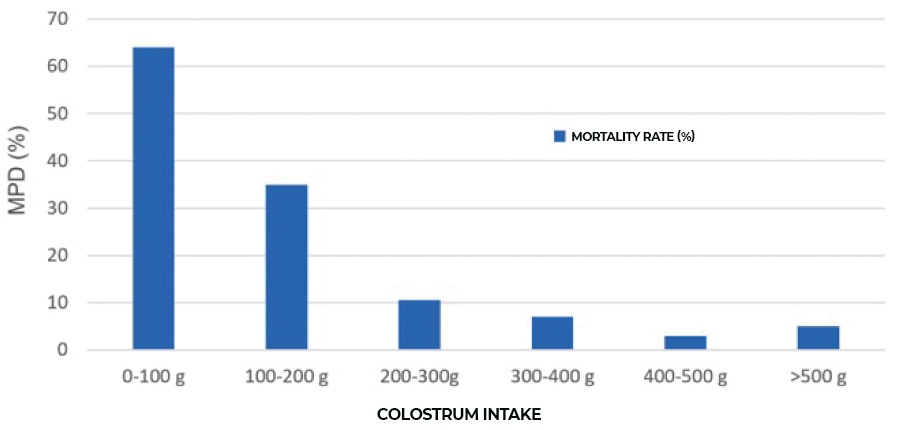

According to a study by Andersen (2007) farms that performed shift-loading of smaller piglets had lower mortality rates than those that did not. They also found that 72% of the piglets that died before weaning, although most died crushed, had not ingested colostrum. Thorup (2013) showed that turn-based colostrum increases piglet survival by 0.4 (Table 1).

Table 1: Colostrum intake is directly related to mortality rate.

Once they are well heated, it is advisable to have an adoptive sow pick up the small piglets, because it helps to decrease competition with their older siblings. According to the study by Cecchinato et al. (2008), in adopted piglets, the probability of survival increases by 40% compared to piglets of litters in which no changes are made.

Mobile NI-2 Nests and Corner of Rotecna

In addition to the advantages offered by the nest for piglets and sows, they are of great help to keepers, since they meet the necessary qualities to provide a space of thermal comfort to hypothermic piglets and to establish shifts colostrum thanks to the closing mobile fences, in addition to being an ideal shelter to protect the piglets from the risk of being crushed when the sow lies down. Vasdal et al. (2010) studied what made a nest more attractive to piglets during the 72 hours after calving. The study was carried out by comparing three types of nests, with different bed materials, with or without a roof to conserve heat, and with or without the use of lamps. They concluded that the greatest increase in its use was due to the ceiling and the bedding material (paper, mat ...).

"The control, observation and care of calving are essential to concentrate on everything that can happen."

Conclusions

With the current genetics, high prolificacy is a proven fact, as is the added problem of small and immature piglets increase and its consequences: augmented probabilities of casualties. Calving caregivers must act to try to minimise such losses. To do this, they must acquire the awareness and perseverance necessary to believe that they will obtain positive results (although some of them are not tangible in an immediate way) with their contributions and not faint in the effort to continue with their mission: to save the maximum number of piglets. Their success depends on them and the means at their disposal. The control, observation and care of calving are essential to concentrate on everything that can happen and act quickly. During this process, time is money. The priority is there. The first 12 hours are vital. Not all of them will be saved, there are completely unviable ones and births do not always occur during working hours, but there is no excuse if they occur during working hours. Well-heated piglets are equal to healthier animals with optimal growth capacities (all their lives) thanks to the better development of their immune system.

Farms with low percentages of casualties prioritise body temperature control and the colostrum of the piglets systematically and routinely. If this is emphasised, their effort is compensated with very positive results. And, in turn, we improve animal welfare by preventing piglets from dying that can survive if they receive proper care.