Blog

Blog

Advantages of the Feeding Ball in the weaning-to-breeding period

29th August 2018 - Studies

The period between the day sows are weaned and when they start breeding is short but very important for ovulation and fertilization in sows. During this time, it is recommended that sows should be exposed to a minimum number of hours of light of a certain intensity so that the weaning-to-breeding period is shortened and oestrus is more intense. Feeding also plays a very important role in this period. Sows are typically coming out of a catabolic state in lactation, so we are interested in getting them to an anabolic state as quickly as possible, so as not to affect productivity. That's why experts recommend ad-libitum feeding (known as flushing) in the weaning-oestrus phase, to achieve good follicular development, which will produce a greater quantity and quality of oocytes and will obtain more numerous and more homogeneous litters.

In practice, we find that the farmers tend to ration all sows in the same way, and generally tending towards less rather than more, in order not to have to raise dispensers as they are entering oestrus and also to avoid having to remove excess feed from the pan. Other farmers choose to wean the sows in pens with hoppers, but one of the main disadvantages of this system is aggression and problems with aplomb. A possible solution for all these issues is to design a specific area for this period, where the sows are housed in separate cages with the Feeding Ball as a mechanism for individual feeding. This prevents fighting, and we get more individualized control of feed consumption and guarantee the maximum potential intake by each animal with the minimum waste of feed.

It must be borne in mind that feed consumption during the weaning-breeding phase varies in accordance with different parameters: some are intrinsic to each sow, such as the delivery number, and others are external, such as the ambient temperature. There are also changes in consumption on certain days within the weaning-oestrus period, for as the sow approaches oestrus, her feed consumption tends to go down. Ad libitum feeding with mechanisms such as the Feeding Ball caters for this variability in intake, while reducing feed wastage, without supposing any additional cost in labour.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

To test the functionality of this mechanism in the weaning-breeding phase, we conducted an experimental trial on a commercial farm owned by the Vall Companys company. The piglet production farm, Albiporc SLU, has 635 Nucleus genetic sows and works in weekly bands. In the test, we evaluated the consumption by a total of 376 sows, divided into 16 herds (April-August 2015). In each herd, sows were randomly distributed depending on the thickness of backfat and delivery number in the two treatments: Feeding Ball (feeding ad libitum, with a limit of 6 kg/intake) and Control (feeding by hand using the farm's normal protocol, 4 kg/day). This feeding pattern was applied from the day of weaning, only considering afternoons, since in the mornings they received their food in farrowing pens, and until Saturday (day 4), when the majority of sows went into oestrus and they all started to be given 2 kg/day. After controlling feed consumption in the weaning-breeding phase, the results were monitored for going into oestrus and percentage of births. We also recorded prolificacy at the following delivery and weighed piglets individually at birth to obtain the average weight and variability within each litter. The results were analysed with the Infostat statistical software, considering treatment as a fixed effect, the herd and the interaction of the herd with the treatment as random effects, the birth as a general covariate of the different parameters and the total piglets born as a covariate in the parameters related to piglet weight.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results obtained by the test show that the Feeding Ball is a mechanism that can optimize feed consumption during the weaning-to-breeding period. During this period, the sows with the Feeding Ball device consumed on average 1.3 kg more per day than the Control pigs. This average consumption of 5.3 kg/day is difficult for most farmers to achieve. In the best cases, the usual level is about 4 kg/day (as in the Control test). These figures could still be increased if the consumption is measured in winter, when high ambient temperatures do not reduce sows' appetite. Within the days of the weaning-oestrus period, the day of weaning and the following day are those when we most limit consumption by equalling rations, with statistically significant differences with respect to the Control, while the two days prior to going into oestrus, consumption of 4 kg/day fits quite well.

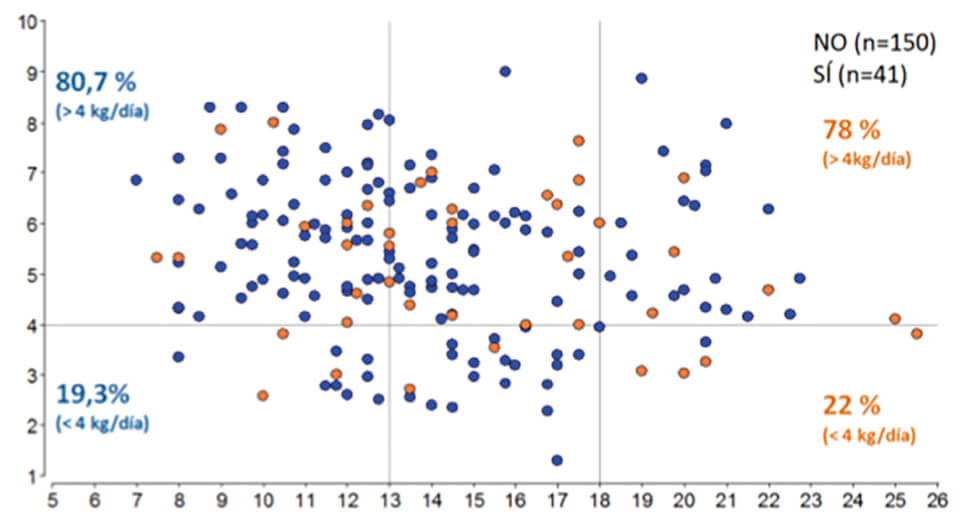

Some people claim that there is no need to re-feed sows on weaning day, but this test shows that there is still potential consumption (almost 5 kg), if the sow has feed available. Another factor to be highlighted and that helps to encourage consumption during this period is that the animals should not have trouble adapting to the mechanism, even without prior contact. In fact, the proportion of sows consuming less than 4 kg/day was even somewhat lower in sows that had not previously been in contact with the system (some farrowing pens had the Feeding Ball installed) than in those that had had prior contact in lactation, which shows that this device is intuitive of this species' natural rooting habit (Figure 1).

Despite the higher feed consumption that is achieved with the Feeding Ball during the weaning-breeding period, no statistically significant differences were observed in the subsequent results for going into oestrus, prolificacy and birth weight of the following delivery. Even so, parameters such as the percentage of births (Table 2) and the prolificacy of the following litter were numerically superior.

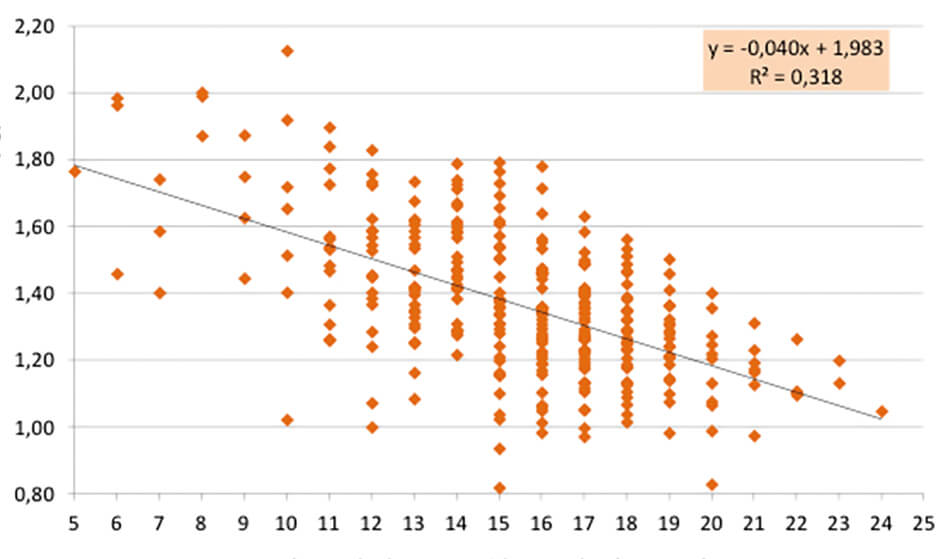

The sows that ate ad libitum using the Feeding Ball in the weaning-mating period gave birth to 0.42 more piglets per delivery (Table 3), without any negative effect on the weight of the piglets at birth, when it is well known that piglet weight is around 40 g less per additional piglet in the litter (Figure 2). Neither were differences observed in weight variability within the litter between treatments, despite the higher total number of piglets born. In the overall data between both treatments, almost 20% of the weighed piglets were less than 1 kg at birth and about 12% of weighed piglets were heavier than 1.8 kg.

Therefore, not only is birth weight important, but also the homogeneity within the litter. Piglets weighing less than 1 kg can amount to as much as a third of the litter when it is very large (more than 20 piglets born in total). These piglets, if they survive lactation, are to a large extent a drawback in transition and fattening, because they lengthen the time of barn occupancy until they achieve the desired weight for being sent to the slaughterhouse.

CONCLUSIONS

The weaning-breeding period is short and delicate, and plays a key role in sow productivity. During these days, it is recommended that sow intake should be rationed, hence the Feeding Ball is a useful tool to maximize the real consumption of feed, and it minimizes wasage. It not only adapts feeding to each animal, but also adaptation to the mechanism poses no problem, even without prior contact. With equal rations in the weaning-breeding period, the day of weaning and the following day are the ones when we most limit voluntary intake by sows. A sow clearly will not not eat if not given the opportunity. Although we have not observed a statistically significant improvement in later reproductive outcomes as a result of increased feed consumption during postweaning, there is a numeric improvement in the percentage of births and prolificacy at the following delivery. Sows fed with the Feeding Ball gave birth to an average of 0.42 more piglets per delivery, without any negative effect on birth weight or weight homogeneity within the litter. It is not clear whether the lack of statistical differences in the parameters for production is due to the sample of animals not being large enough or whether or not consumption of more than 4 kg/day during the weaning-breeding period offers compensation to the farmer in terms of subsequent production. There is always the possibility of increasing the sample size and repeating the test in winter, when the differences in consumption would be more marked.